European Green Bond Standard – A new Gold Standard for saving the planet?

- Dr. Dennis Heuer, LL.M.

- Partner, White & Case

- Claire-Marie Mallad, LL.M.

- Local-Partner, White & Case

Zitiervorschlag: Heuer/Mallad, LRZ 2023, Rn. 851, [●], www.lrz.legal/2023Rn851.

Permanente Kurz-URL: LRZ.legal/2023Rn851

"Just as railways revolutionised 19th-century America, envision a revived Capital Markets Union propelling Europe forward in the face of contemporary challenges." Emphasising this parallel, Christine Lagarde recently highlighted the importance of advancing a European Capital Markets Union – an ambition taking concrete shape with the introduction of the European Green Bond Standard (EGBS). This article examines the legal framework of the EGBS and provides a brief overview of green securitisation.

1. Introduction and previous practice

Few topics have maintained their grip on political and societal conversations as persistently as the question of how to combat man-made climate change. While politicians worldwide are pursuing diverse yet often determined approaches to this challenge, the question of the right path is also resurfacing at the European level.

The solution: the European Green Deal. Behind this concise catchphrase lies a series of measures designed to position Europe as the world's first climate-neutral continent. Legally, this package of measures is predominantly supported by the EU Green Finance Framework, a set of standards for the economy of the future.

One of the more recent measures aimed at implementing the so-called European Green Deal, a package of initiatives in European capital markets1, is the European Green Bond Standard (EGBS). As the European Commission hopes to establish a new “gold standard”2, this article will shed light on the latest regulations.

1.1. EU legislation on sustainable finance – EU Green Finance Framework

The European Union's recent legislative efforts in the fight against climate change can be summarised under the banner of the EU Green Finance Framework. This includes a wide range of regulations aimed at promoting a more sustainable economy in various sectors. The key components of this framework are (i) the Taxonomy Regulation3 and (ii) the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)4.5

The Taxonomy Regulation’s primary objective is to minimise the information asymmetry that typically exists between a purchaser and a seller by aligning the meaning of the term “sustainability”, with a view to optimising the allocation of resources. The Taxonomy Regulation is also important as a reference point for other regulations.6

In addition, comprehensive reporting requirements are intended to facilitate the exchange of information. The CSRD requires national legislators to transpose the Directive into national law by mid-2024. Reporting requirements will be phased in, starting with all companies that are already required to produce a 'non-financial statement'.7 By 2025, all large companies will be required to provide relevant information. In 2026, small and medium-sized listed companies will also be affected.

1.2. Present market standard

The concept of sustainable business practices is not limited to the realms of politics and research. The trend towards sustainable living and asset allocation has influenced the decision-making levels of the business world. Companies across various sectors are eager to assume the role of responsible trailblazers.8 When offering bonds, more and more issuers opt to issue them with a certain pre-determined use of proceeds – so called green bonds.

Green bonds refer to bonds that are dedicated to a specific sustainable purpose. The primary objective of green bonds is to encourage capital market investments in favour of environmentally friendly objectives. Key distinctions from conventional bonds primarily lie in their earmarked purpose, while the structural and yield expectations often bear similarities.

In 2022, green bonds worldwide reached a total volume of nearly $500 billion.9 Remarkably, Germany, despite having fewer issuers, ranks as the third-largest market for green issuances.

However, amidst the encouraging developments for sustainable business goals, it is essential to note that the classification of whether a bond is genuinely “green” or sustainable remains subject to interpretation. Companies independently determine whether one of their bonds qualifies as “green”. Although this determination is often made with the assistance of reputable institutions that establish general rules and criteria, it still relies on a degree of trust in the issuing companies.

The concern of many investors has merged under the term “greenwashing”, which underscores the worry that companies may be incentivised to present facts in a light that portrays their products as sustainable and environmentally friendly, even if they do not genuinely meet the criteria for such labelling.

2. European Green Bond Standard

Green bonds, which have firmly established themselves as a part of the capital markets, ultimately require regulatory action on the part of the legislator. In response to market criticism, which had highlighted the lack of a universally accepted definition for sustainable bond issuances10, the European legislator recognised this as a comparatively straightforward endeavour, especially when contrasted with other measures, such as investment commitments. The provision of a unified standard, serving not only the development of meaningful definitions and criteria, but also safeguarding investor trust, is expected to play an active role in the European bond markets in the near future. This is intended to promote increased investment confidence across the board.

2.1. Background

2.1.1. Necessity of regulation and possible approaches

Investment in sustainable technologies is essential in the fight against man-made climate change. In Germany alone, according to estimates from a study by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (Ministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz), the country will require between €280 billion and €900 billion by 2050 for its commitment against climate change.11 The costs have reached such proportions that relying solely on government taxation and levies is no longer deemed sufficient. The influx of financial resources from the private sector is not just a desirable development, but an integral part of the campaign.

The absence of trustworthy and universally accepted standards creates an information asymmetry between investors and issuers. Investors are required to place a significant level of trust in the issuer because they cannot otherwise be certain of the accuracy or significance of the information provided.12 While trust in companies is not uncommon, investors may find themselves dependent on a potential buyer in the secondary market who also relies on the issuer's statements when selling their investment.

Investors are left with the option of conducting extensive research and information gathering to verify the authenticity of the issuer's claims, although this may not eliminate the risk of reduced attractiveness in the secondary market. To completely eliminate the risk, investors would need to disregard the “green attribute” in their investment considerations. Often, this renders a bond unable to compete with others.

While legislative measures can take various forms, it is commendable that the European legislator is favouring market-based principles over enforcing a preferred course of action through bans and obligations. It is particularly noteworthy that there is no obligation for issuers to designate green bonds as EGBS; instead, the utilisation of the EGBS label remains a voluntary decision, thereby broadening the range of potential actions. While the EGBS must compete in a free market against other standards, it does not displace those applicants who genuinely aspire to engage in sustainable economic activities but do not meet or choose not to meet the EGBS's criteria.

2.1.2. History

The inception of EGBS can be traced back to a 2018 report by the European Commission aimed at fostering sustainable economic growth. The establishment of an expert commission, which consistently provided interim reports and saw active participation in the “Green Bond”-project, ultimately led to a legislative proposal by the European Commission in 2021.

While the European Parliament initially responded to the European Commission's proposal with significant reservations, calling for a more comprehensive regulation13, an agreement was reached in early 2023. This agreement, which was then debated in the EU Parliament, marked a significant milestone.14

Apart from the European Parliament, criticism of the planned introduction of the EGBS was relatively muted. Notable input on the proposal was also provided by the German Bundesrat15 and the relevant legislative bodies of Spain16, Portugal17, and the Czech Republic18. Particularly the Bundesrat emphasised in its statement that the inclusion of the free market was a commendable decision by the European Union. While expressing a fundamentally positive stance, the Bundesrat did provide a few points of criticism and improvement suggestions, such as extending the deadlines for asset allocation requirements. Some of these points, in some cases going beyond the Bundesrat's proposals, have been incorporated into the latest version of the proposal.

On 23 October 2023, the Council of the European Union has adopted the legislative proposal, signalling a consensus in alignment with the European Parliament.19 The EGBS will come into force 20 days after it is signed and published in the Official Journal of the EU. The regulation will then be applicable 12 months after its entry into force.

2.2. Main provisions

2.2.1. Introducing a new and reliable market standard

The green market of the future must consist of well-defined frameworks and clearly articulated criteria. Only through such clarity can an issuer's statement convey a meaningful impression to investors. The law accomplishes this criterion by referencing the Taxonomy Regulation. As mentioned above, the Taxonomy Regulation serves as a point of reference for various regulations in defining terms.

Although it may initially appear surprising that a general regulation seems to provide answers to the complex mechanisms of the capital markets, the reference to the Taxonomy Regulation is plausible. While it might seem more fitting to use different definitions for various sectors on a case-by-case basis, this approach would significantly impede the harmonisation of terminologies.

Employing this referencing technique offers noteworthy benefits. It reduces legal uncertainties for all transaction participants dealing with consistent terminology under different regulations. It also grants smaller issuers flexibility in customising their financial products efficiently. Without such an approach, where each transaction must comply with various green bond standards from diverse regulations, issuers might be discouraged from issuing green bonds.

2.2.2. Taxonomy-compliant utilisation of proceeds

Article 6 of the EGBS regulation prescribes the taxonomy-compliant utilisation of proceeds generated through the issuance of bonds in the capital markets. Among its core objectives, the regulation aims not only to standardise terminologies (as described in point (a)) but also to establish a pivotal reference point for evaluation.

2.2.3. Third-Party Review

As previously described above, information asymmetry arises not only from differing interpretations of terminologies and the resulting risk of misconceptions but also from the reduced trust an investor can place in information originating from the issuer. Neglecting to address this issue poses the risk that the solutions presented above may not be credibly integrated into the capital markets. Such a course of action would encounter immense challenges that could ultimately lead to its failure.

The European legislator is taking a radical approach in this regard. Instead of merely requiring the recording and provision of information20, information will be subject to examination and confirmation by independent third parties. This approach is akin to the concept of credit rating agencies.

While third-party assessments for financial products were commonly used prior to the EGBS, their involvement will become mandatory for the utilisation of the EGBS. These third parties are private institutions that must register with the relevant European authority (the European Securities and Markets Authority – ESMA) and are subject to its supervision. External assessors must demonstrate substantial organisational arrangements and meet requirements for sufficient expertise. They are not only obligated to develop appropriate and standardised evaluation processes and keep them functioning, including from a technical perspective, but also to ensure the qualifications of their staff. The specific market standard for such external assessors remains largely within ESMA's discretion.

2.3. Affected sectors

Sectors that have previously issued green bonds are particularly affected by the new framework. While the use of the EGBS is not mandatory, both issuers and investors are increasingly contemplating the permissibility of resorting to alternative green bond standards. Sectors significantly impacted include real estate, energy, waste management, and transportation. These areas, although frequently debated in everyday life, are equally relevant in the realm of a sustainable economy. So far, renewable energy technology manufacturers and real estate companies in the United States have primarily participated in issuing green bonds, effectively dominating this segment of the capital markets.

For Germany, a more intriguing question may revolve around the potential for adoption within the machinery and automotive industry. This sector shows considerable promise, especially considering that a significant portion of its products are acquired through financing or leasing arrangements and could potentially become compliant investment assets.

3. European Green Bond Standard and Securitisation

3.1. Securitisation and its potential in the efforts to combat global warming

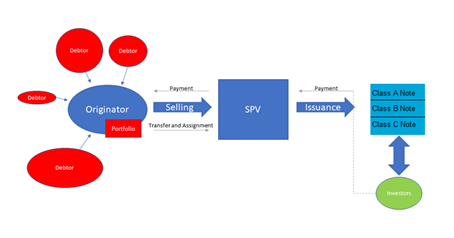

Securitisation primarily means the transformation of illiquid assets into tradable securities. When a pool of claims is securitised, it becomes tradable, enabling investors to participate in the pool by acquiring a bond. With respect to traditional securitisations21, the following chart illustrates the usual structure:

The originators aggregate assets owed to them, for example loan receivables, which, as a whole, constitute a portfolio. This portfolio is transferred to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), a legal entity established solely for the purpose of the transaction. The SPV issues tranches of debt securities22 in the capital markets, which are backed by the portfolio (Asset-Backed Securities or ABS) and finances the purchase price owed for the receivables to the originator with the resulting proceeds. Through the SPV, investors are protected from the insolvency of the originator, while the originator does not necessarily have to be liable with its remaining assets in the event of a portfolio default.23 This process is often used for risk mitigation, capital relief and refinancing/liquidity purposes.

In order to understand the opportunities and possibilities that securitisation transactions offer for sustainable practices, it is essential to consider the fundamental differences between securitisation bonds and unsecured bonds. While the issuance of unsecured bonds prompts investors to assess the financial condition of the respective issuer, an ABS transaction is characterised by the fact that the issued bond is backed by a pool of specific assets, so that the insolvency of the originator, as the economic initiator of the transaction, becomes irrelevant.

In this context, the following two crucial points emerge that should not be overlooked in their implications for sustainable actions.

3.1.1. Pool-orientation

Firstly, securitisation is pool-oriented, meaning that investors base their investment decisions not on the issuer's credit rating but on (the rating of) the specific asset pool. This is particularly relevant in the banking sector, where banks operate in various segments with varying sustainability impacts. If an investor wishes to invest in unsecured bonds, they typically focus on the creditworthiness of the banking institution. The disadvantage for the bank is that improving its rating is impossible within a short period. However, when the investor's decision is dependent on the rating of an asset pool, the bank can compose a pool of suitable assets with a good credit outlook that can be securitised.

For banks that have thus far inadequately delved into the business of green bonds, this provides an opportunity to engage with the green economy without necessitating significant changes to their business models. This ensures that banks do not incur substantial risks by undergoing a major reorientation in their business practices while still participating in green financing. Securitisation transactions can serve as a driving force, providing banks with the necessary confidence to make their overall business models more environmentally friendly.

In this context, it is important to underline the essential role of banks in financing green investments, which are crucial for tackling the climate crisis, in particular for decarbonisation efforts. Especially in the European bank-based system, banks play a pivotal role when it comes to financing of the real economy. Companies, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises, rarely or never finance themselves through the capital markets but instead opt for traditional bank financing. It is essential to note that banks have onerous capital requirements when lending. Securitisation allows banks to transfer some risk to investors, release capital and unlock additional lending. This additional lending will be needed for financing green investment.

Concluding one can say that securitisation makes resources available for lending that were previously unavailable. As a result, a securitisation market with particular focus on green securitisation is key in order to realise the urgently needed investment in sustainable projects.

3.1.2. Current industrial landscape

The advantage of a swift and less risky granting of purpose-specific loans becomes particularly apparent when considering the industrial landscape. While the outright purchase of automobiles or machinery is becoming increasingly rare (not only for businesses but also for consumers), leasing and financing options have now become integral components of the industry. In-house banks of manufacturers are, therefore, holders of a multitude of receivables suitable for securitisation.

By securitising such receivables, manufacturers can, in a short period, offer new leasing and financing options under the aforementioned advantages, made possible by the proceeds from the securitisation transaction. Considering the potential for the development of new environmentally friendly and sustainable technologies, manufacturers can, through the swift influx of capital, provide financing opportunities for these products. This, in turn, can facilitate the market establishment of innovative technology and increase consumer willingness to make purchases.

3.2. Securitisation and the EGBS

The fact that the securitisation market plays a crucial role in increasing the volume of green investment was recently highlighted by the president of the European Central Bank (ECB), Christine Lagarde. She explicitly advocated strengthening the European securitisation market to meet the challenges of inter alia decarbonisation:24 “A genuine CMU (Capital Market Union) would mean building a sufficiently large securitisation market, allowing banks to transfer some risk to investors, release capital and unlock additional lending. In the United States, banks have access to a securitisation market that is three times the size of Europe’s. This could be even more powerful in our bank-based financial system.” Against this background, it is a particularly good sign that the European legislator has opted to include securitisation within the EGBS, recognising its potential.

The main provision related to securitisation is set out in Article 6a of the regulation, stating that the provisions regarding the use of proceeds should apply to the originator rather than the SPV as issuer of the asset-backed bonds.25

Given that only the originator has an operative business this makes sense. Compliance with the EGBS principles is determined mainly based on the use of proceeds the originator receives from the purchase price vis-à-vis the SPV, rather than based on the characteristics of the underlying assets.

The underlying exposures are only referred to in Article 18 of the EGBS regulation, which declares particularly environmentally harmful assets as incompatible with the EGBS. This may seem surprising at a first glance, as otherwise only the use of proceeds is taken into account. Upon closer examination, however, this is understandable. If one aims to establish the EGBS as a credible label on which investors can rely, it would be difficult to justify that environmentally harmful assets become “green” simply because the bonds issued in a related securitisation transaction are used for sustainable purposes.

While the EGBS regulation does not introduce significant changes in the legal framework of securitisations in the European market, issuers of securitisation bonds would be wise to explore the new possibilities offered by the EGBS. Whether this can lead to a competitive securitisation market in Europe remains to be seen over time. Overall, it is a positive sign that securitisations were not excluded from the regulation, and originators and issuers can resort to the EGBS within securitisation transactions.

4. Conclusion

In most cases, a legislative proposal within the European Parliament encounters far more opposition. The European legislator has succeeded in crafting a consistent and well-thought-out law. The integration of the capital markets into the challenges of climate change represents a significant step towards a holistic solution.

While the European Commission's goal of establishing a new “gold standard” with the EGBS may sound ambitious at first, at least in terms of raising awareness and the balance of the regulation, one cannot fault the European legislator for not making a sincere effort. Ultimately, the responsibility for creating sustainable capital markets lies with the respective stakeholders, including us as society.